El Dorado is the story of a mythical city of gold that has been the inspiration for several expeditions into the wilds of South America. If you are like me, you read in a

Weekly Reader at some young point in your academic career that "El Dorado" was a mistranslation that led the Spanish public, and the rest of history, to confuse a term for a man covered in gold with a wealthy city. It turns out that explanation is

not entirely correct. The real answer to the El Dorado myth, is a bit more complex.

El Dorado and the Lost City of Z

According to Willie Drye of National Geographic, the Spanish heard about men being covered in gold in the 16th century. What became our mythical El Dorado was the culture and assumed city this man lived in. Any culture that could afford to throw precious items into a lake (to appease a god, of course) and coat a man in gold probably had a pretty impressive city to call home.

The term "El Dorado" refers to the "gilded one," the man himself, in Spanish. The amount of gold found in South America led to the assumption that there must be some fairly civilized, complex city on the continent supplying all of it. While there were

cultures in Central and South America with the wealth that could be the answer to El Dorado, explorers were not appeased. This was the beginning of a search for civilization in the mass of jungles that make up the Amazon.

|

Lt. Col. Percy Fawcett in 1911.

via Wikimedia. |

Lt. Colonel Percy Fawcett was an English explorer who held several dangerous jobs through out his life time. (Also, the subject of an

upcoming film starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Robert Pattinson.) He is famous for a number of achievements, including seven successful expeditions into the Amazon rain forest, mapping the much contested source of a Brazilian river, and making

grand claims about

wildlife.

When Fawcett went on an expedition with his son and his son's young friend to find what the Lt. Colonel had dubbed the "city of Z" in 1925, no one doubted their ability. The party disappeared without a trace soon after. In its wake, around 100 explorers have gone missing attempting to find the Fawcett Party.

Is there some dark secret surrounding the "lost city?" There are plenty of terrifying stories that follow. One of my favorites is that of a minor actor turned pathfinder that went trailblazing in search of Fawcett. The last correspondence received from Albert de Winton was carried by a runner out of the rainforest on a crumpled piece of paper. A plea for someone to bring help, and to save him from the tribe he had been captured by was scribbled on the page. He was never heard from again. It was later learned that his head had been smashed in with a club for his rifle by a

Kamayura tribesman.

As exciting as a lost city defense system would be, the real reason for missing parties probably has more to do with logistics. To put things in perspective: What is considered the Amazon rainforest is about one half the size of the United States, and over twice as large as the United Kingdom (excuse me while I make assumptions about my readership). That is a lot of ground to cover. While Fawcett left some coordinates behind, and the last place he was seen before disappearing is known David Grann, while researching for his book

The Lost City of Z, discovered the coordinates were fake. This was to guard against explorers attempting to find the city before Fawcett.

Even an experienced adventurer could get lost. That being said, many of those that went in search were much less than experienced, and likely had unrealistic expectations of themselves or their surroundings. Piranha are scary enough, but like many other rich habitats on Earth, the Amazon is full of poisonous plants. Also, the possibility for diseases a newcomer would not know how to handle, much less avoid. Not to mention people that could be less than happy to see you. Indeed, while traveling through the home regions of the indigenous groups, it is still important to know which ones are friendly.

Civilization

Fawcett's conviction that there had been a civilization of amazing complexity locked away somewhere in Brazil was drawn heavily from what Grann calls a "widely held belief" of the time: that such a civilization sprouted from European influence somewhere much earlier in history. Fawcett thought that the Pheonicians, or even the denizens of Atlantis (a mythical city first written about by Greek philosopher Plato,) had traveled to South America and inspired a stone city deep in the jungle. This assumption tells us a lot about Western archaeology.

First of all, in Victorian England (and also before and after, in the West), the assumption was that people like those living in and around the Amazon region were primitive, and locked in a stage of precivilization. This meant that the tribes Fawcett interacted with on his expeditions were seen as a lower rung of an assumed natural line of evolution towards what Europe had achieved. When talking about archaeological history, it is important to learn the term "e

urocentric."

Eurocentrism is the basis for much of what I mean when I refer to "our" archaeological understanding of the world. The assumptions held by Fawcett and other people of his time are based on the accepted wisdom that Europe is the birthplace of civilization. There are many shades and complexities to the ideas surrounding this, but for now, keep this simple idea in mind as we progress forward.

I feel it is also noteworthy that the cultures Fawcett cited as possibly founding civilization on this faraway continent are often considered part of the Orient, or Near East. As discussed in

an earlier post, Europeans have often appropriated foreign cultures, in this case as the basis for their impressively civilized state. At the same time these cultures were separated from Western ones as an exotic curiosity. Thus Fawcett was appropriating a culture in order to push his unfounded beliefs on another one.

|

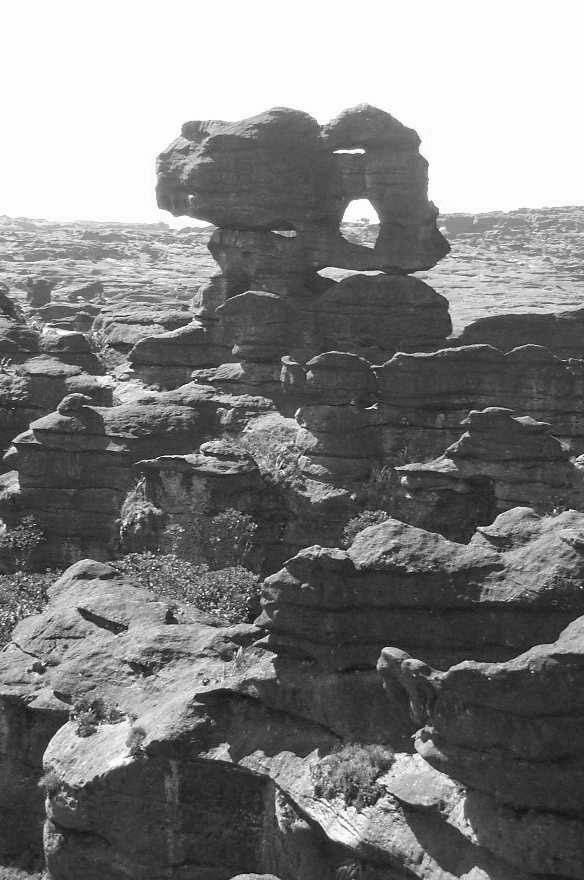

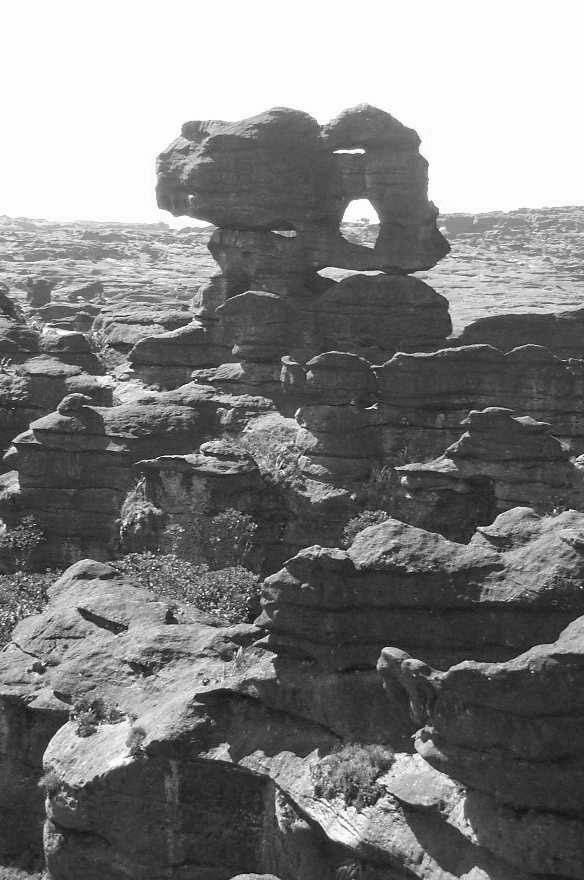

Rock formation from the Tepui plateau.

photo by Jeff Johnson

via Wikimedia. |

Fawcett believed that he would find stone ruins in the jungle. Part of this was again based on the eurocentric ideas of the day, and partially on accounts of stone structures reported by earlier explorers. As Grann explains, these accounts may have been based on naturally occurring eroded sandstone formations that curiously look like the ruins of buildings. While the

remains of wood dwellings had been discovered in Europe during the previous century, the majority of sites were made in stone. To be fair, it is rare that wood survives the eons as well as stone.

Many sites in Europe are rich in permanent building resources. This is true in parts of South America, too. However, in the forest, wood is much more plentiful. While Fawcett's theory may have been based on centuries of false assumptions by Europeans, he was very close to the truth. There have been urban settlements in the rainforest.

These settlements were carefully planned, and had populations in the thousands. About

20 of them have been found by Professor Michael Heckenberger of the University of Florida. They were not like anything Fawcett suspected. In fact, they were much grander.

Each site was surrounded by moats and walls, and was connected to other sites by roads and bridges placed at right angles. Proof of these sites lay in the ditches dug for the circular moats, and the holes left by the evenly spaced poles of the walls (or possibly defensive pits). Records of these sites have also been preserved in history, though not in ways we might look for. People local to the area, specifically the Kuikuro, have preserved the history of these great cities in their oral history through myths. It also retains the first time they came in contact with Europeans in 1750. What followed was slavery and epidemic disease for indigenous populations.

Perception and Eating Human Brains

I have referenced David Grann's book and work a couple of times through out this post. The information I have offered is only a fraction of the full story of the search for Z, and all it ensnared. The book is fantastic, though there is also a summary of the author's adventure in the footsteps of Fawcett

available on the website of

The New Yorker. It is truly a story about asking the right questions.

However, there are less enlightened responses to the search for the city of Z. Perhaps more in line with Fawcett's contemporaries, is

Rich Cohen of the New York Times. In his review of

The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, he recites popular opinion of the people living in the region without a grain of irony, calling the Amazon a place "where hunter-gatherers still lived on human brains".

I am no expert on cannibalism. I will admit that now. However, there is no possible way that a diet of human brains is sustainable. We grow too slowly, and it takes too long for us to reach maturity. Where would all the brains come from? If every, or even a few of the groups within the Amazon subsisted on brains, who would be left to gather the remainder of the diet? The human brain only has

about 200 calories (per adult brain). While it is a heavy source of protein, where are the other 1,800 calories that are supposed to go into a healthy daily diet to come from?

If your answer was still "gathering," let me tell you something just as mind-blowing: many groups in the Amazon have been

practicing agriculture for a long time. We hear a lot today about cattle farming and agriculture clearing incredible amounts of land every single minute. This is not the agriculture I am talking about.

Indigenous people in the Amazon Rainforest practice slash and burn agriculture. They keep the land healthy by rotating where they are growing crops every few years. There goes the myth of pure hunter-gatherers in the "new Eden" that the Americas were supposed to be.

The urban centers that Heckenberger found also disproves the notion that Amazonian tribes always lived furtively in the forests, existing in complete symbiosis. At least once in time, an indigenous group collected resources and cleared the forest to build on a massive scale. My point with this breakdown is that culturally accepted discourses (or ways of thinking about other groups) are often not factually based. Instead, they mirror our culture's desires and needs for what we perceive as Other. Cohen played on what we believe these groups to be like in order to hook us for the rest of his article.

I have done it myself. By describing "expeditions into the wilds of South America" I was playing on what is probably your vision of South America: primitive, dangerous, unknown. This turn of phrase is not always incorrect (I have to sell this article somehow, after all), but it is good to be aware of the ultimate effect of using what we perceive as factual about an exotic land.

It says something about us that the myth of a golden city has survived so long. Interest in the physical evidence of cultures that have survived in a place as foreboding to us as the Amazon Rainforest has peaked and plummeted again and again, but the idea that they may have at one time approached what we would consider civilization is what captures. I think it is time for us to dispel the noble myths we hold about ourselves.

Sources

Mcleod, John. Beginning Postcolonialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

_2011-09-02_15-07-42.jpg)